The Vanished Prince

In the footsteps of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Howard Scherry never met his mentor. The legendary French aviator and author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry had long since disappeared into the sky in a P-38 Lightning over the Mediterran-ean, presumed dead. It was 1956, intermediate French class. The reading assignment included a stray passage from Saint-Exupéry’s Wind, Sand and Stars. Its cadences and message of friendship had a hypnotizing effect on the 19-year-old UVA. student. “It is as if Saint-Exupéry took me by the hand and said to me: ‘You will follow me, young man; you will accompany me for the rest of your life,’” Scherry (Col ’60) says.

Now 70, Scherry still carries that used French textbook, Contes Modernes, like some private talisman. The paper clip is still there, marking the page that opened into a lifetime of scholarship about the man who wrote The Little Prince. But after a brief academic sprint—he wrote his undergraduate thesis on Saint-Exupéry, graduated Phi Beta Kappa and earned a master’s degree in French at Stanford University—Scherry’s study became more idiosyncratic. His method has been to dig beneath chronological events, to track down and befriend the many people who crossed paths with Saint-Exupéry. It’s been a backward-roving treasure hunt. Only the starting point is fixed: July 31, 1944, when Saint-Exupéry vanished without a trace during an Allied reconnaissance mission.

Scherry notes that most people are unaware that Saint-Exupéry was actually a New York author. He wrote his classic fairy tale, The Little Prince, while living in New York, from 1941 to 1943. It was a dark and lonely period of self-exile that nevertheless proved his most productive; he also wrote Flight to Arras and Letter to a Hostage during this time. A lucid tale about the child-prince from asteroid B-612 who leaves his tiny planet and visits an aviator stranded in the Sahara, The Little Prince features a philosophical fox, a serviceable snake and an assembly of amiable but anxiety-ridden adults.“It is only with the heart that one can see rightly,” the fox tells the prince. “What is essential is invisible to the eye.”

“It is as if Saint-Exupéry took me by the hand and said to me: ‘You will follow me, young man; you will accompany me for the rest of your life.’”

A slim book, it has a pathos that can bring a reader to tears easily. It’s a distillation of a lifetime of experience, according to Scherry, and couches secrets and symbols from Saint-Exupéry’s past. All the characters are traceable—even the odd-looking fox, which resembles the fennec that he encountered as a young man in the North African desert. “You will find more fact than fiction in his tale,” Scherry says.

Many people profess that they cannot tell whether it is a book for children. Scherry believes he intended it “as an autobiography in a childlike framework, with anthropomorphic characters.” Saint-Exupéry didn’t provide any guidance. The Little Prince was published two weeks before he returned to active duty, and he was never interviewed.

If it’s a book in a category of its own, so too is Scherry. He’s considered a Saint-Exupéry scholar and has lectured internationally about him, though he’s an American without a Ph.D. after his name. He has advised Saint-Exupéry biographer, Stacy Schiff, and other journalists, but his own book-length manuscript has languished without a publisher. The organization he founded, Remembering Saint-Exupéry, has, he says, “a general but no army.” While he lets it be known that Le Souvenir Français recognized him with a bronze medal for his endeavors, he delights in putting it into proper perspective: “The Légion d’Honneur is the highest decoration in France,” he explains, “but I have the lowest medal in France.”

Still, he’s made it into the pages of the New Yorker and the New York Times over the years. He helped persuade the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York to display, for the first time, the original working manuscript of The Little Prince on the 40th anniversary of its publication. Written on onionskin, covered with preliminary sketches and the residues of coffee and cigarettes, it was illuminating if unreadable. “You can’t decipher the writing, even with the strongest microscope. It’s worse than hieroglyphics,” Scherry says. “You admit defeat.”

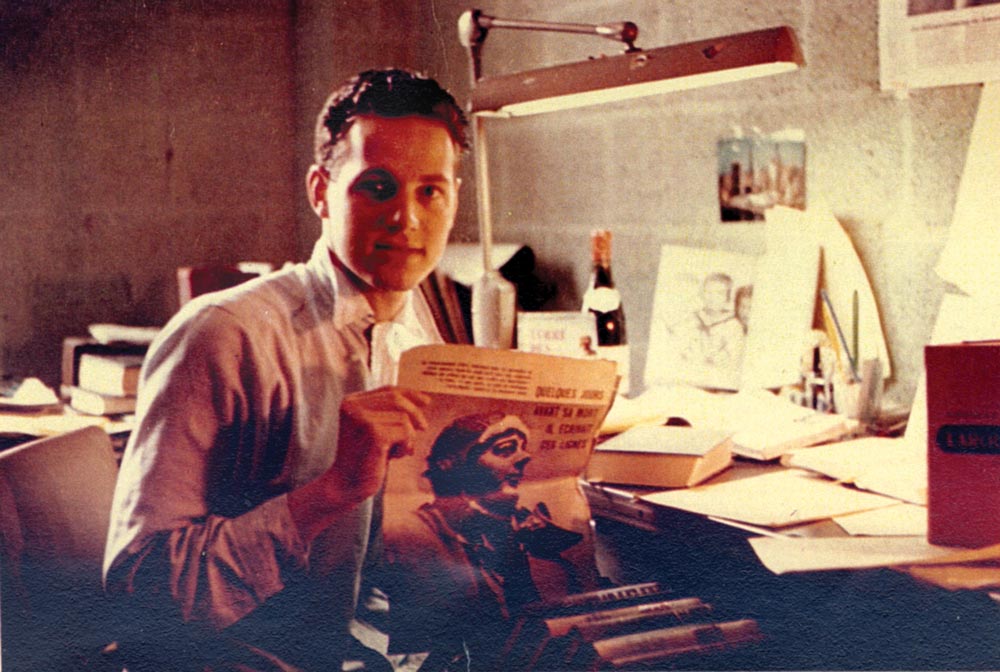

A native New Yorker, Scherry also started conducting literary walks around the city—in English and French—taking people on a circuit of Saint-Exupéry haunts. He can tell you where Saint-Exupéry bought a Dictaphone for $700 (on a shopping spree originally to buy an organ); where he attended Christmas Eve mass in 1942 (and his opinion of the service); plus so many other arcane facts that the New York Times declared, “Mr. Scherry speaks with such eloquence and humor about Saint-Exupéry that it is hard not to imagine the two as lifelong friends.” In 2000, after a lengthy campaign headed by Scherry, a commemorative plaque was placed at 3 East 52nd Street in Manhattan. It was here, in the studio of his friend Bernard Lamotte, that Saint-Exupéry holed himself up to write many of the chapters that became The Little Prince.

Within Scherry’s archive are papers from Saint-Exupéry’s secretary, Marcelle Bouchu, who typed many of his manuscripts, including The Little Prince. Elderly and living in the Bronx when Scherry found her, her apartment was a forgotten trove of Saint-Exupéry material no one else had seen. Shortly before she died, she entrusted much of it to Scherry, including a poignant letter that she saved from oblivion, a missive Saint-Exupéry wrote to his wife then threw away. It’s this largesse that Scherry says he will continue to travel just about anywhere to share.

“My own adventures could be a book,” he says, musing aloud, “but what would the title be?”

The following excerpt is from “Antoine de Saint-Exupéry and The Little Prince: You Can Go Home Again—In Your Memory” by Howard Scherry, from his lecture commemorating the 50th anniversary of The Little Prince, given before the Association Culturelle Francophone in New York.

“Saint-Exupéry’s child, so to speak, exists timelessly young in each and every page of The Little Prince. Saint-Exupéry’s child is a literary offspring. Authors do give birth, you know, to their books. A subliminal attachment links the pilot and the prince. Man to child, father to son, a parental bond grows in the Sahara desert. During the writing of his tale, it falls to Saint-Exupéry to live the exceptional love. A love transcending the usual definition of love. He holds in his hands and he carries in his heart an integral part of the heavens whence the little prince has come to land on Earth. Only the author accompanies the prince through the desert. Saint-Exupéry both bathes and beams in the welcoming warmth of their meeting of souls. Yet, how very much we, the readers, are enriched since we are witnesses made wiser, I should hope, by the story of their exceptional encounter. As all grownups are first children, all relationships first begin as encounters, and when such an initial encounter is nurtured with that unique person, it can become our own fairy tale lived factually each and every day.

The little prince can be seen as symbolizing potentially certain childhood characteristics: children’s fragility, their freshness, their spontaneity, their lack of fear, their enthusiastic readiness for experience rather than a hesitant backing away from confrontation with life, and let us not forget, a very unique youthful trait, their inquisitiveness, at times indiscreet. As you recall, the little prince never gave up on a question unless and until he received a satisfactory answer. All these characteristics are the virtues of innocence contrasted with the “vices” of maturity. All qualities of Antoine himself who enjoyed the most privileged youth at the turn of the century. To take advantage of walks in Provence such as those taken by young Antoine, or to take “advantage of the migration of a flock of wild birds” in the manner of the little prince in exploring the world. It is all one and the same for a child. Here is a passage from Flight to Arras where, at 40 years old, Saint-Exupéry reflects on the nostalgia of youth: “When I was a small boy … I speak of my early childhood, that is to say, of a vast region out of which all men emerge. Where do I come from? I come from my childhood. I come from my childhood as from a homeland.”

Not to be an outgrowth of one’s long and loving childhood is to admit one is born too soon an adult.

What Saint-Exupéry yearned for throughout his all-too-short life was the warmth of human relations not unlike the relationship between the fox and the little prince, and between the little prince and the pilot. And, of course, the warm relationship between the little prince and his flower. But the little prince’s rose is a female. Very much a female. She has the right to act like a female. That means: the flower/rose/female has her own priorities. There, complications enter. Now, we must enter into these complications. All is not going well between the little prince and his rose. Or to phrase it another way, nothing is going right between the little prince and his rose. In fact, the little prince is extremely vulnerable and he becomes a hostage to love for his rose who has “only four thorns to protect herself against the world.” Where the little prince is concerned, you could even say that four thorns are three thorns too many.”

Howard Scherry is founder of Remembering Saint-Exupéry, which has as its mission to foster and further the memory and message of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. He has lectured widely about The Little Prince. If you would like him to speak before your group, please contact him at 212-787-3586, saintexb612@yahoo.com or by regular mail at 243 West End Ave., New York, NY 10023.