The Power of Normal

UVA changing misperceptions, behavior with social norms campaign

Every month or so, hundreds of copies of a unique publication arrive in first-year dorms around UVA. Volunteers post the one-page journal, bubbling with a lively array of news and information, in places where it can’t be ignored.

It’s called the Stall Seat Journal for a reason, and Marisa Mutty (Engr ’12) looks forward to reading it when she heeds Mother Nature’s call in Bonnycastle House.

“I love the Stall Seat Journal. I memorize the whole thing,” says Mutty. “It gives you good tips.”Such as this quotation, playfully attributed to Thomas Jefferson in the October edition: “Hey, Buddy. What’s up? Check this out—89 percent of UVA first years usually or always make sure they don’t leave a friend who has been drinking alone with a stranger.”

There’s more, including bus routes, the phone number for a tobacco “quit line,” details about “safe” events around town and more alcohol-related statistics.The facts are the tip of an iceberg of data used in social norms marketing, a field slightly more than two decades old and growing in acceptance and prominence. With the move of the National Social Norms Institute to UVA in 2006, the University has became a central player in social norms research, resources and education.

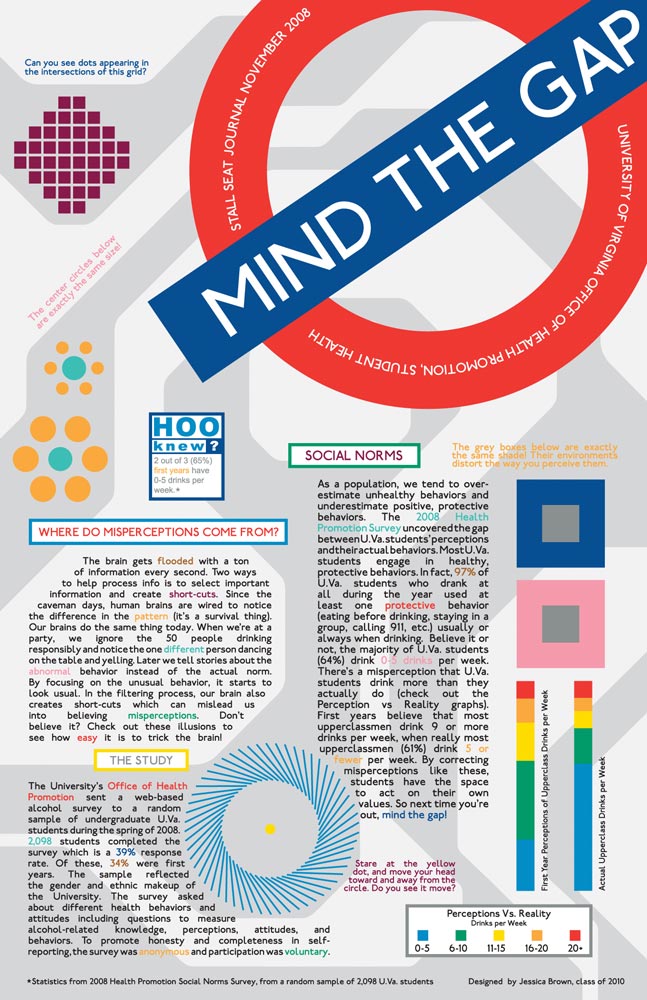

The approach revolves around identifying what’s normal among peers in a certain population, such as the UVA student body, through anonymous surveys and other research. This information is used to combat common misperceptions—such as first years believing that UVA students in general are heavy drinkers—that can feed negative behavior.

“The idea of social norms is that there is a gap between what they think their peers are doing and what they’re actually doing. And it’s in that gap that there is movement,” says Dr. James Turner, executive director both of NSNI and of UVA’s Department of Student Health.

“It’s a paradigm shift,” says Jennifer Bauerle (Educ ’00, ’03), director of the institute. “It’s really shifting people’s thought patterns about how they look at health.”

A six-year study released this summer documents how that shift is taking place at UVA. Students exposed to social norms marketing showed dramatic decreases in the negative consequences of alcohol-related behavior—driving under the influence, injuries, unprotected sex.

Replacing “health terrorism”

Social norms marketing does away with the draconian images of “health terrorism”—images of crumpled cars shown to scare people into being safer drivers. Instead, statistics compiled through painstaking research are presented in carefully designed marketing campaigns.

“Social norms is simply about telling the truth about what people are doing,” Bauerle says.

So, what are UVA students doing? According to HooKnew? (the UVA social norms marketing program):

60 percent have an average of zero to five drinks per week (15.4 percent have zero drinks per week).

75.6 percent usually intervene to stop friends from drinking and driving.

83.5 percent always call 911 if someone they’re with is showing signs of alcohol poisoning.

The point is that it’s normal to call 911, normal to intervene, normal not to be a heavy drinker. That last bit gains significance when considering that first years who were surveyed overestimated by more than double the amount they believed students were drinking at UVA.

Of taxes and hotel linens

While alcohol consumption holds center stage in many social norms campaigns, research has explored a vast landscape of topics—tax compliance, seatbelt use, gambling, even reusing hotel linens.

Perceptions, whether right or wrong, are one of the strongest predictors of behavior. As Turner put it to a group of fourth years taking a class at the Curry School of Education, “What you think your friends and peers do is very important in motivating you to do that. False perceptions are just as powerful as true perceptions,” he said, using a presentation chocked with numbers, graphs and, yes, even quotations from Thomas Jefferson.

Does social norms marketing work? The approach has its critics, most prominently Henry Wechsler of the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study. In the 2002 book Dying to Drink: Confronting Binge Drinking on College Campuses, Wechsler and co-author Bernice Wuethrich argue that the basic assumptions of social norms programs are unproven, that statistics don’t reflect behavior in smaller peer groups (which have greater influence on a person’s choices), that norms tend to encourage abstainers to drink, and that funding for research comes largely through the alcohol industry, thus compromising the data.

Indeed, Anheuser-Busch in particular has provided significant funding. It helped finance the opening of the National Social Norms Resource Center at Northern Illinois University in 2000. When the institute moved to UVA, Anheuser-Busch supplied a $2.5 million five-year gift to continue research.

Turner and Bauerle stress that Anheuser-Busch, recently purchased by InBev, has a completely hands-off approach to the research. And they credit John Nau (Col ’68), who is president and CEO of a Texas beer distributorship, with helping to secure funding at UVA that dates to 1999.

Turner remembers a talk he gave at Alumni Hall that year. The UVA community was still grieving the alcohol-related death of a 21-year-old student two years earlier. After the presentation, Nau asked Turner, “You want more funding to do your social norms marketing?”

That year the Stall Seat Journal was born, and with it an effort that has grown in scope and sophistication. NSNI (“Nisney” to insiders) now partners with eight other universities in its research, and it coordinates a national conference each year that provides researchers a forum to share information.

“The institute has an extremely important role in the advancement of the field,” says Alan Berkowitz, a New York psychologist and a founding father of the social norms field. “In addition to the national conference, the institute can serve as a catalyst to sense the state of the field, stimulate research and technical assistance, and help the field evolve in a positive direction. I am extremely pleased with the work that UVA has done in all of these areas.”

The institute’s efforts extend beyond the hallowed grounds of higher education. Bauerle is consulting with Albemarle County about campaigns in its schools, and this spring she heads to Belgium for a European Union forum.

“Social norms is in its infancy in Europe, and there’s an interest in using more social norms methodology,” Bauerle says.

That methodology is framing inquiry in far-flung fields. One Australian researcher looked into perceptions of tax compliance—do people cheat on their taxes because they perceive others do? He found that in many cases people overestimated how much others fudged on their taxes and reduced their personal tax deduction claims when they learned the norm. To a large degree, though, a person’s moral beliefs dictated compliance.

Another study looked at the impact of using social norms marketing to encourage people to reuse hotel linens. Researchers found that a social norms message—“Almost 75 percent of guests who are asked to participate in our new resource savings program do help by using their towels more than once”—placed in hotel rooms led to increased linen reuse rates.

Watershed study at UVA

Though research is exploring other fields, alcohol abuse among young adults remains a primary focus.

A watershed event in that regard occurred this summer for NSNI. Turner and Bauerle co-authored, with H. Wesley Perkins of Hobart and William Smith Colleges, an article in the peer-reviewed Journal of American College Health detailing results of a campus survey involving thousands of UVA students from 2001 to 2006. The researchers asked students who had been exposed to social norms marketing efforts to respond anonymously about 10 alcohol-related consequences, from having unprotected sex to driving after drinking.

The results: Over the six years of the study, odds of experiencing none of the 10 alcohol-related consequences nearly doubled, and multiple consequences decreased by more than half for all undergrads. Turner has added data from the past two years to come up with numbers that compare 2008 to 2001:

- 2,000 fewer UVA students suffered injuries related to alcohol in 2008 compared to 2001.

- 1,500 fewer students drove under the influence of alcohol.

- 2,500 more students had none of 10 serious alcohol-related consequences.

“We believe that the social norms marketing campaign has really had a fairly dramatic impact on the students at our university,” Turner says.

The institute isn’t alone in its efforts at UVA. The Center for Alcohol and Substance Education, under the Office of the Dean of Students, is a vigorous partner in coordinating University-wide prevention efforts and spreading the word about behavior regarding alcohol, tobacco use and sexual activity.

Unlike NSNI, the center’s funding comes from UVA and is supplemented by grants from the National Collegiate Athletic Association, the U.S. Department of Education and the National Institutes of Health, says director Susie Bruce (Col ’89, Educ ’91). Smaller groups—athletic teams, fraternities and sororities—are the targets of their social norms efforts, and, like NSNI, the focus is on helping students make safe choices.

Bruce has been using a social norms approach for years, and she’s seen changes on several fronts. Students are less skeptical of the statistics, and the University’s approach has matured. The Stall Seat Journal’s message goes beyond alcohol. “The campaign now, I believe, has a nice balance,” she says.

Protective behavior gets prime emphasis, and it’s not just in a do-good fashion. Small cards showing blood alcohol concentration levels for men and women have found their way into many students’ pockets.

“I actually think that’s really cool,” says fourth-year James Anderson, a resident adviser at Bonnycastle House. “It’s really effective.”

The cards plot blood alcohol concentration levels over time, factoring in a person’s weight and the number of drinks consumed.

Do you know your BAC?

Turner and Bruce hope the cards convey two central points. First, not all drinks are equal. Blood alcohol levels jump dramatically at a certain point. Second, the potential for negative consequences—drunken driving, blackouts, unprotected sex, violence—increases just as dramatically.

“We really do focus on negative consequences, and that’s where we get the student buy-in,” says Bruce. “If you’re having 12 drinks, you’re more likely to have a fight and other problems than if you’re having three or four drinks.”

Such information goes a long way, Anderson says, but he says the best lesson comes when someone has a bad experience themselves.

“My experience as an RA is that that’s where I see the change,” he says. “That said, I think the Stall Seat Journal actually does generate conversation. People talk about it, and that’s one of the most effective things you can do.”

Bauerle agrees. “It [the Stall Seat Journal] is really a conversation with our population,” she says.

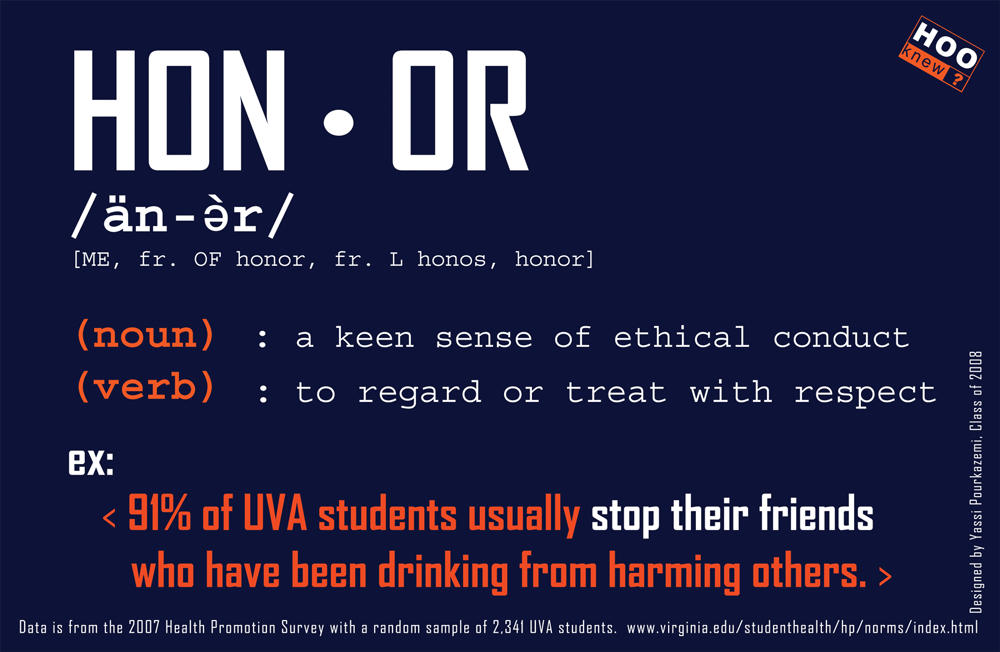

Anderson also sees a flip side to the social norms approach. He cited a poster saying that 91 percent of UVA students usually stop their friends who have been drinking from harming others.

“I can see what they’re getting at, but to me that means that one in 10 wouldn’t step in to intervene,” says Anderson, who is from Australia. “If you’re looking at the effectiveness of social norms, that means that out of every 10 people, one won’t stop their mates from trying to bash somebody else.”

No one, including Turner, claims that the approach constitutes a panacea. “That’s like saying chemotherapy does or does not work for treating cancer.”

A specialist in internal medicine, Turner likens the method to a clinical setting, where a doctor lays out information for a patient, describing the possibilities and potential consequences.

There’s evidence beyond UVA, though, that the approach is good medicine. In an article this summer about the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, the Boston Globe reported, “Two years after launching the so-called social norms campaign, health officials say they are seeing striking results, with recent student surveys indicating a sharp decline in binge drinking. The university has coupled the marketing with tighter regulations and enforcement, as well as expanded prevention services.”

Laura Nix, a fourth-year who listened to Turner’s presentation at Curry, says the concept of addressing misperceptions is effective. She remembers the impact of reading the Stall Seat Journal her first year.

“The whole social norms thing—people are blown away by it.”