The Night Of

It began as the quintessential college field trip, a day filled with learning, laughter and genuine kindness. It ended with three shot dead, two wounded and a student charged with murder. What happened?

Note: This account of the events of Nov. 13, 2022, includes details of shootings and may be upsetting to some readers.

Mike Hollins (Col ’23) didn’t expect to be on the field trip, let alone that bus.

For two weeks his close friend and University of Virginia football teammate D’Sean Perry (Col ’23) had been working him, begging him, to join Perry’s drama class to see a play and spend the day in Washington, D.C. Hollins had no interest, leaving aside that he’d never been to Washington, never seen a professional play. The all-day venture was planned for Nov. 13, deep into the football season and the Sunday after the game against a tough University of Pittsburgh team.

But Perry persisted right up to the last minute, the morning of, telling Hollins a spot had opened. Hollins gave up saying no, collected his book bag and headed off with Perry for the adventure.

Hollins expresses no regrets—the opposite, in fact. “I was really happy I went, really happy I spent that time with my boy D’Sean,” he said in an interview on “The Pivot” podcast in mid-December. “I can vividly remember after the play, me and him just standing outside, you know downtown D.C., outside of the theater, just taking it all in. It was freezing cold. I was just telling him how glad I was that he pulled me out of the house.”

Hours later, as the group returned to Grounds from what should have been the kind of college experience that inspires a lifetime of nostalgia, someone aboard the charter bus opened fire. The shooter, a student, witnesses say, killed Perry along with teammates Devin Chandler (Col ’24) and Lavel Davis Jr. (Col ’24).

Hollins took a bullet himself that evening. It pierced a kidney and his small intestine, a shot in the back that missed his spine by 2 centimeters, he told an interviewer. Second-year student Marlee Morgan (Col ’25) suffered injuries as well, less serious than Hollins’, though the details have stayed private. She hasn’t talked publicly about the events. Nor has a fifth football player on the bus, who escaped amid the gunfire.

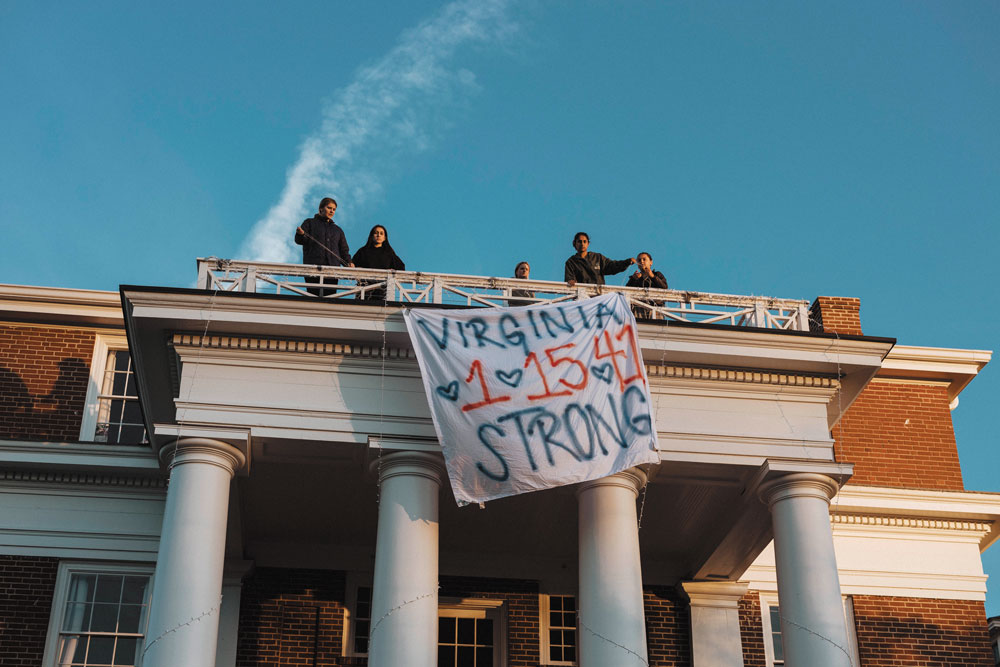

Months later, the trauma remains raw and real, the communal sense of loss still profound. The day after the shooting, not yet 24 hours after the horror, thousands of students congregated on the South Lawn for a candlelight vigil. On seemingly telepathic cue, they illuminated their battery-powered candles and raised them to the sky row by row, creating a wave. Because the steady inflow of mourners had overwhelmed the supply of the devices, students improvised with their own, lifting high their mobile phone flashlights. It made for a moment of stunning sight and soundlessness.

Virginia Magazine took a similarly muted approach in this round of our reporting of the still-developing story. Those involved continue to heal from injuries both physical and emotional. Much of the making and the aftermath of Nov. 13 remains unknown. The criminal investigation and an external review are just getting underway.

Before attempting to explore the big questions, the how and the why of senseless gun violence visited upon, and allegedly by, UVA’s own, we set out to answer a more basic one: What happened that night? In reconstructing events, we purposely avoided approaching the families of the victims, the survivors or other potential witnesses. We relied primarily on published reports, the public record, interviews that have appeared in other media and what we could piece together on our own. The more we learned, the more it broke our hearts.

All Aboard

The bus for the field trip boarded around 11:30 a.m. outside the drama building on Culbreth Road, the Arts Grounds thruway that winds around the back of Carr’s Hill. Second-year student Ryan Lynch (Col ’25) arrived with a sense of anticipation, not just for the school trip but also for who would show up for it. She had transferred to UVA in the fall from historically Black Hampton University on the Virginia coast, which meant she was new and still making friends. She told The Washington Post’s William Wan she had become particularly close to the football players in the class, including Chandler, Davis and Perry.

She wasn’t sure they would be there, especially since they had had a football game the day before. Pitt’s 37-7 drubbing of the Cavaliers, their third consecutive loss and the season’s worst, wouldn’t have seemed to help her cause. But Chandler, a wide receiver, didn’t play; he hadn’t all season since transferring from the University of Wisconsin. Week Two of a concussion protocol sidelined Davis, a playmaker wideout. Perry, a linebacker, did get playing time. Hollins, a running back, did too, but Lynch may not have known him or even expected him since he wasn’t in the class. To her delight, the lot of them turned out for the show.

Theresa M. Davis, associate professor of cross-cultural performance, arranged the outing for DRAM 3070, her African American theater class. The word Lynch used to describe Davis was “charismatic.” An anonymous reviewer on Rate My Professors elaborated: “Lady T … genuinely radiates a genuine warmth, positivity, and interest and love for the material she teaches.”

True to those traits, the professor opened the cultural experience to students in her other class that term, an upper-level performance directed study called “Speaking Social Justice.” That was how the accused shooter, Christopher Darnell Jones Jr. (Col ’22), a fourth-year who hadn’t graduated last spring, came to join the group.

Jones boarded the bus along with the others on that brisk and breezy mostly sunny late morning in Charlottesville, the temperature having already reached its high and beginning its steady descent toward the cold night. The doors shut and the group, 22 students by some reports, Davis and the bus driver, headed up the road to the Atlas Performing Arts Center in northeast Washington to see The Ballad of Emmett Till.

Acts of Kindness

The play depicts Emmett Till’s final days, the lynching of the 14-year-old Chicagoan in Mississippi in the summer of 1955. The play, part of a trilogy about Till’s life and importance to the civil rights movement, features an all-Black ensemble cast playing multiple parts in the past and the present.

Curtain time was 3 p.m. The UVA students sat together, but not Jones. He sat by himself, toward the front of the house. “But it didn’t seem very unusual because he wasn’t in our class actually,” Lynch told anchor Linsey Davis (Col ’99) of ABC News Live Prime.

Professor Davis made sure the day’s cultural experience didn’t end with the show. She arranged for the group to enjoy an authentic Ethiopian meal, less than a mile down H Street from the theater, at Ethiopic Restaurant. The group spread across several tables on the restaurant’s heated, glass-enclosed patio, proprietor Meseret Bekele told Virginia Magazine. She worked with Davis in planning the menu: several platters to give the students a good spectrum of the aromatic cuisine, largely vegetarian, with chicken, fish and meat offerings and different appetizers.

“I’m not going to say I liked everything, but it was a good time,” Hollins told former NFL safety Ryan Clark, one of the hosts of “The Pivot” who has known Hollins since his childhood. “It’s hard to think about that, in hindsight … on this end of the tragedy. It’s hard to think of the important times that we had right before, that you had a great play, a great dinner.”

With similar retrospect, after news of the tragedy and pictures of Jones reached Washington and the rest of the country, Bekele says the woman who served the students told her she remembered the student accused of the shooting. “He didn’t actually eat. He didn’t actually want to do anything. He was just sitting there,” Bekele says her staff member told her. “He didn’t look happy.”

(The server was in Ethiopia for an annual religious celebration, Bekele told us, and couldn’t be reached.)

Bekele was struck by the kindness of the students. “They were just young kids, just trying to try something new,” she says. The tip for the meal was included, had been worked out weeks before. Even so, the students took up a collection at the end and left their server more than $100. “She was really touched by it,” Bekele says. “You could tell that they were very, very sweet.”

It is the thank-you card they left behind that makes her heart ache. Everyone signed it, saying how much they enjoyed the meal and that they’d be sure to come back. Bekele says, “Just looking at that card just really broke us—when we actually figure out what happened to those kids, you know, who said they would be back.”

The Last Hours of Normal

The group left Ethiopic about 7:45 p.m. Once on the road, students sang gospel, Hollins remembered. From Lynch’s account in the Post, Devin Chandler connected his phone to the bus sound system and cranked up the latest Drake album. Professor Davis made a face at some of the profanity. “Don’t worry! I got a song for you,” Chandler told her. He queued up an old-school R&B tune, which had Davis dancing in her seat in appreciation.

Hollins spent some of the time doing homework. Lynch remembered him helping her with hers.

Jones kept to himself, toward the back, Lynch said. About 30 minutes out of Charlottesville, Lynch headed his way to use the bathroom. She struck up a conversation. She knew him from Fashion for a Cause, a UVA fundraiser where they both had tried out as runway models in September.

“Hey Chris, did you do the fashion show? Are you doing any modeling,” she recalled saying. “There’s one in the spring. You should try and do that one with me.” He said he might, Lynch said in the ABC News interview.

Lynch remembered some of the football players heading to the bathroom in the back. She didn’t know of any of them to have interacted with Jones. Nothing has come to light suggesting any of the victims knew the accused gunman before the trip. Jones’ few months as a nonplaying member of the fall 2018 football team ended one year before Perry and Hollins came to UVA, two years before Lavel Davis arrived, and four years before Chandler transferred in. None appears to have been a member of Kappa Alpha Psi, the historically Black fraternity where Jones served as UVA chapter president.

“How well did you know him?” ABC’s Michael Strahan asked Hollins on Good Morning America in December.

“I didn’t know him. I didn’t know him at all.”

“At all,” Strahan repeated for emphasis.

As the bus neared Charlottesville, Hollins remembered most of his teammates being asleep in the back, only natural since they had football practice the next morning. Hollins did too, but he padded about the bus with his shoes off. He saw the professor starting to tidy things up, collecting the snacks that had been handed out and packing up boxes. He joined in to help her. Together, they gathered up that day’s last remnants of normal.

Shots Ring Out

The bus would have turned off University Avenue, motored up Culbreth Road and curved right at the parking deck to make its slow approach toward the drama building, based on photos of where it ended up. Hollins said he had packed up his things—presumably others were milling about doing the same—and had moved toward the front of the bus.

Shots rang out around 10:15 p.m., according to news reports. In interviews, Hollins and Lynch separately said they initially mistook the sound for someone’s popping small bags of chips. But Lynch’s ears wouldn’t stop ringing, and then she smelled the acrid discharge, according to the Post. She dropped to the floor and covered herself with her jacket and a blanket.

Jones didn’t shoot at random but targeted the three players, Davis, Perry and a still-asleep Devin Chandler, shooting each in the head, Albemarle County Commonwealth’s Attorney James M. Hingeley (Law ’76) said at a preliminary court hearing three days later, according to press reports.

Lynch said Jones spoke just before firing, saying, “You guys are always messing with me,” or something like it, or so people told her afterward. “But that doesn’t make sense because no one was really talking to him the whole trip,” she told the Post.

Hollins remembered seeing Lavel Davis go down. The Cavaliers’ 6-foot-7, 210-pound wide receiver, clad that day in a bright orange hoodie, fell into the aisle. “He was a very tall human, a very big human,” Hollins said on “The Pivot,” where he described Jones standing over the body as “just, you know, overkill.”

Hollins said the bus was still moving during the shooting. He pushed past Theresa Davis and confronted the driver. “It took some choice words from me to the bus driver, to get him to understand that, you know, he gotta stop, he gotta let these kids off.”

As soon as the doors pulled open, Hollins, along with the unidentified teammate on the trip, sprinted off the bus. The other player ran to safety. Hollins stopped.

“I knew I didn’t get off with who I got on with,” he told “The Pivot.” He had left Perry behind. Hollins turned around to get back on the bus. “My boy D’Sean was the only person on my mind in that moment.”

Hollins said he got as far as two or three steps when he came face-to-face with Jones getting off the bus. “We locked eyes, and it was just a cold look,” he said in the Good Morning America interview, “just like a numb look.”

He said he saw Jones raise the gun toward him. Hollins, still shoeless, dropped the book bag and phone he had been clutching, spun around, and ran.

Lynch, crouched on the bus floor and peeking out from under her wraps, had just seen Jones stride past her toward the front of the bus. She told the Post she heard him fire shots as he got off.

Hollins, running flat out, felt a bullet pierce his back but he didn’t slow. “He was going to have to hit more than once for me to stop,” Hollins said.

Hollins fled into the Culbreth garage and ran up past the first level. When he realized he wasn’t being chased, he came back down. When he got to the bottom and looked down, he saw a bullet hanging out of his gut.

It was then, he said, that a woman came to him, a pre-med student. “She was there to help me. She kept me calm, kept my breathing under control, was checking my pulse until the ambulance came,” Hollins said. She hasn’t been named publicly. In interviews, Hollins credits God.

Back aboard the bus, Lynch and a friend tried to render aid to Lavel Davis. He lay facedown in the aisle, his pulse barely detectable. Lynch said stains on the orange sweatshirt made him look riddled with gunshots. She saw a bullet hole in his head and one in his back. The two women were going to perform CPR but thought better of it, worried about the risks of trying to move someone in his state. “Lavel, we’re trying to help you,” Lynch recalled saying. “There’s nothing we can do right now, but we’re going to get help for you.”

With Jones having left the scene, the teacher called for everyone to evacuate the bus, Lynch said.

Lynch told ABC News: “Every single one of the guys, there was someone on that bus who tried to help them before we had to get off. So, I just want their families to know someone was with them. One of us was with them after they were shot, and we loved them so much.”

Police arrived on the scene around 10:30 p.m.

Phones Explode

The University community at large received its first security alert at 10:32 p.m. “UVA Alert: Shots fired reported at Culbreth Garage. … If possible, avoid the area,” said the message, pushed out to students, faculty and staff, anyone with a valid UVA computer network account. Students can add family members to their alerts account, which means some parents received an email or a text too. (With mass distribution messaging, time stamps can vary by recipient.)

Seven minutes later came the lockdown directive that would grip the community for the next 12 hours: “1 suspect at large, shelter in place.”

Four minutes later: “ACTIVE ATTACKER firearm reported in area of Culbreth Road. RUN HIDE FIGHT.”

With the hunt for Jones underway, the alerts got successively more specific. At 11:07 p.m. the suspect was generically described as “ARMED AND DANGEROUS.” Three minutes later came a physical description: “BLACK MALE, WEARING A BURGANDY [sic] JACKET OR HOODIE, BLUE JEANS, AND RED SHOES.”

At 1:19 a.m., Nov. 14, the authorities provided a name: “SUSPECT IS CHRISTOPHER DARNELL JONES JR.” Twenty-eight minutes later came a vehicle description, black SUV, and a Virginia tag number.

Throughout the early morning, messages noted that Virginia State Police helicopters had joined the search and told everyone to “EXPECT INCREASED LAW ENFORCEMENT PRESENCE.” In all, phones exploded with close to 60 alerts, many of them repetitive.

The worst news came at 3:59 a.m. University President James E. Ryan (Law ’92) announced three students killed, two injured, in a shooting on Grounds. “This is a message any leader hopes never to have to send, and I am devastated that this violence has visited the University of Virginia,” he wrote in a message broadcast through multiple channels. He didn’t name the victims, but he repeated the name of the suspect at large, consistent with the earlier alerts.

And he canceled classes that Monday. Local city and county schools soon did the same. (The public schools would reopen the next day, UVA on Wednesday.)

Sunday’s overnight shelter-in-place didn’t lift until 10:33 a.m. Monday, after authorities had searched and secured UVA’s sprawling facilities and satisfied themselves Jones had fled the premises. Throughout those 12 hours, students hunkered down in their dorm rooms and apartments, some in the libraries and classrooms they happened to occupy when their phones first vibrated with the words “shots fired,” “HIDE,” “ARMED AND DANGEROUS.” (See related story, 12 Hours in the Dark.)

Shortly after 11 a.m., University officials held a news conference. University Police Chief Timothy J. Longo Sr. began his remarks by assuring the public the University would apprehend Jones, even if he had crossed state lines. A Virginia State Police official signaled him. “Pardon me,” Longo said, and stepped away.

Attendees and streaming viewers watched the state lawman come forward and whisper something in Longo’s ear. The chief returned to the mic. He took a beat before speaking.

“Thank you, Captain. We just received information the suspect is in custody,” he said.

The 57th UVA emergency bulletin hit phones at roughly the same time: “UVA UPDATE: Police have the suspect in custody. This is the final alert message.”

Police arrested Jones outside of Richmond, 80 miles from UVA.

Gun Hunting

We don’t know Jones’ perspective of events or the outlines of a defense. Neither he nor his public defender have granted interviews or issued statements. They haven’t yet entered a plea. With bond denied, Jones remains in Albemarle-Charlottesville Regional Jail, awaiting a March 30 preliminary hearing.

The website for Dance’s Sporting Goods, a guns and ammo store within several miles of Jones’ home south of Richmond, includes the slogan “COME ON GETCHA SOME!” Jones tried to do just that, several times during his college years, Richmond Times-Dispatch reporting chronicled.

Dance’s twice refused to sell him a gun, the first time during Jones’ first year at UVA, when he was under 21, too young to buy a handgun in Virginia, but old enough to buy a rifle.

A traffic stop during Jones’ third year caught him with a 9 mm semiautomatic pistol. It’s not clear how he acquired it. He had reached 21 but didn’t have a concealed carry permit. He pleaded no contest to a misdemeanor charge and had to forfeit the weapon.

Jones returned to Dance’s the summer before his fourth year, but the store refused him again because of a flag on his record showing pending felony charges for a hit-and-run. Jones got them reduced to misdemeanors and pleaded no contest, which removed the hold from future reports.

Jones visited Dance’s at least two more times. In February 2022 he bought a Ruger AR-556 rifle, in July a Glock 45 9 mm pistol.

At the scene of the Nov. 13 shootings, investigators did find a handgun, but they haven’t released information about it. A search the following morning of Jones’ dorm room in Bice House turned up the Ruger rifle, a Smith & Wesson pistol, ammunition and other gun paraphernalia, but not the Glock, according to a copy of the search inventory the Charlottesville Daily Progress acquired through Virginia’s Freedom of Information Act.

Jones’ possible possession of firearms reached UVA administrators’ attention in September, during what is described as a Student Affairs investigation into potential hazing. Someone interviewed reported hearing that Jones might have a gun, which UVA expressly forbids on Grounds and in student housing.

That escalated matters to UVA’s Threat Assessment Team, a statutory body created in the aftermath of the 2007 Virginia Tech mass shootings. That query turned up Jones’ earlier plea to carrying a concealed weapon. Jones “repeatedly refused to cooperate” with Student Affairs, University spokesman Brian Coy told The New York Times. Jones’ failure to disclose the concealed-weapon plea constituted a violation of UVA policy. That prompted the Student Affairs office to email him a warning in late October that it would turn the matter over to the student-run University Judiciary Committee, which hadn’t happened by the time of the shooting.

Not Knowing

As these and other facts emerged in the days after the shooting, University Rector Whittington W. Clement (Col ’70, Law ’74) and President Ryan, following closed Board of Visitors meetings, asked the state attorney general to appoint special counsel to conduct an outside review. The AG, Jason S. Miyares, immediately agreed and, with like dispatch, had the Virginia State Patrol take charge of the local criminal investigation.

As the community struggled to heal in the immediate aftermath, so did Mike Hollins. The running back who almost didn’t go on the field trip, almost got away to safety the first time, and almost didn’t the second, lay unconscious in the University hospital, 36 staples in his body and a breathing tube down his throat.

He regained consciousness midweek, not knowing what happened, not knowing if Chandler, Davis or Perry had survived, died or might be recovering a few doors down the hall. “In that moment I just had all the questions in the world and no answers,” he told family friend Ryan Clark on “The Pivot.”

“My teammates’ family, they’ve been grieving for two days without me. Wake up way behind the eight ball. I don’t know anything,” he said, “but I knew I was blessed.” Hollins added, “I pray every morning. I cry every night, just battling that, the why part of it.”