Serious Cinema

At the Virginia Film Festival, the main star is the art of filmmaking itself

Earlier this year, a pair of jewel heists at the Cannes Film Festival shared the stage with the parade of A-list celebrities who walked the red carpet at one of the world’s most glamorous events. The missing jewels, valued at millions of dollars, were stolen before they could be lent to the stars who typically wear borrowed jewelry and clothing during the festival—an opportunity for jewelers and fashion designers to showcase their wares.

Such a daring jewel heist is unlikely in Charlottesville this November during the Virginia Film Festival. While the UVA-sponsored event has no plans to match the celebrity-spotting appeal of high-profile festivals like Cannes, this festival—now entering its 26th year—has become a gem in its own right.

Appearances by famous actors such as Sandra Bullock, Nicolas Cage and Morgan Freeman, as well as cameos by Old Hollywood legends like Gregory Peck and Jimmy Stewart, have added a dose of celebrity fizz over the years to the Virginia Film Festival. But ultimately, the festival emphasizes substance over style.

It has struck a popular chord with a growing audience as a thinking person’s film festival, one that goes deeper than most into the intellectual and societal aspects of film. For the fourth consecutive year last November, the Virginia Film Festival broke its attendance record, logging 42 soldout screenings and events.

Under Kielbasa, the festival’s schedule is ambitious, having expanded to include mentaries, as well as a string of student and community outreach programs over four days every November. And the feedback from UVA and the Charlottesville community suggests that the festival is on the right path.

“What was exciting for me was to come to the University of Virginia and to be able to build a program where the art of filmmaking and the discussion of filmmaking are first and foremost,” Kielbasa says.

The Toughest Ticket in Town

In recent years, the festival has broadened its appeal and outreach efforts. A new partnership with UVA’s Miller Center is an example of Kielbasa’s push to expand the festival’s educational programs.

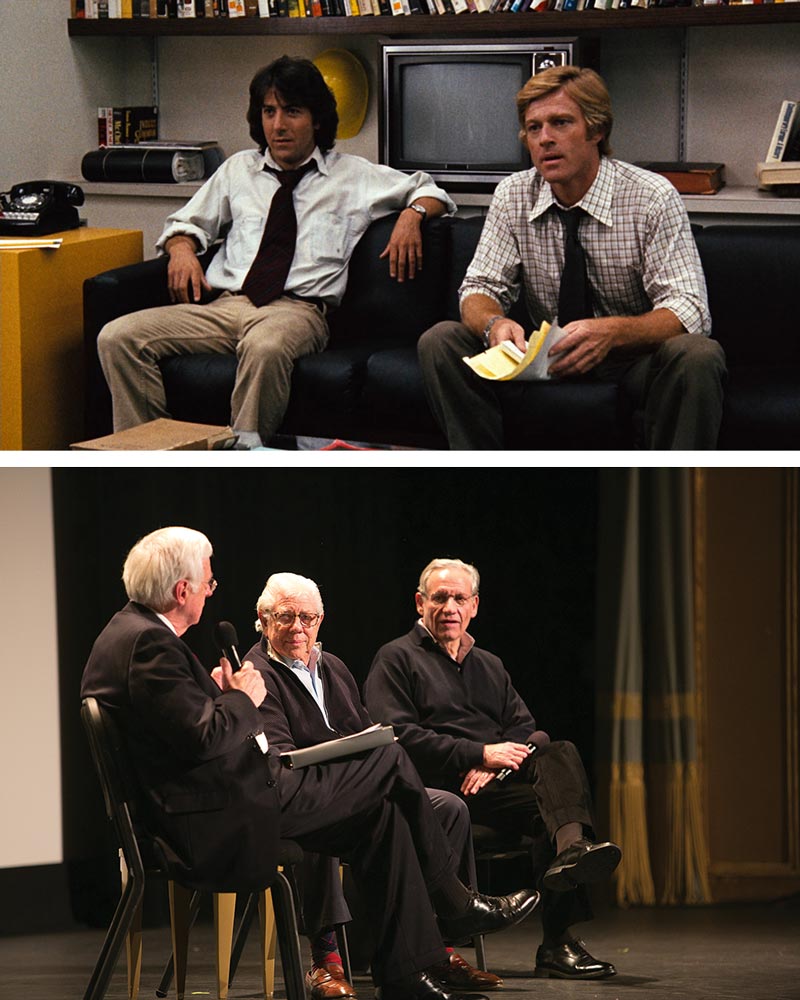

Top: A still from All the President's Men, starring Dustin Hoffman (left) as Carl Bernstein and Robert Redford (right) as Bob Woodward.

Bottom: Former Virginia Gov. Gerald Baliles, Bernstein and Woodward discuss the film on stage at the Paramount Theatre

That Friday night in November, the toughest ticket in town was a rare joint appearance by … two newspapermen. The screening of All the President’s Men—followed by a discussion onstage with reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein moderated by former Virginia Gov. Gerald Baliles (Law ’67)—launched “The Presidency in Film Series,” a new partnership between the festival and the Miller Center.

Barbara Perry (Grad ’86), associate professor and senior fellow in the Miller Center’s Presidential Oral History Program, and Baliles, the director and CEO of the Miller Center, approached Kielbasa about adding an annual selection of films depicting the U.S. presidency, coupled with post-screening discussions moderated by University faculty and experts.

Kicking the series off with All the President’s Men was an obvious, and popular, choice, judging from the soldout screening. A scholar of the American presidency and the U.S. Supreme Court, Perry called it “political science nirvana” to see the Washington Post reporters in person to recount the Watergate investigation.

Woodward and Bernstein drew a standing ovation as they walked onto the Paramount Theater stage. “For months and months, people were telling Gov. Baliles, and I’m sure Jody, and certainly me, that that was one of the most compelling things they’ve seen in Charlottesville,” Perry says.

The Festival’s Roots

Baliles was instrumental in launching the festival during his tenure as governor, as were former University president Robert O’Neil and lead supporter Patricia Kluge.

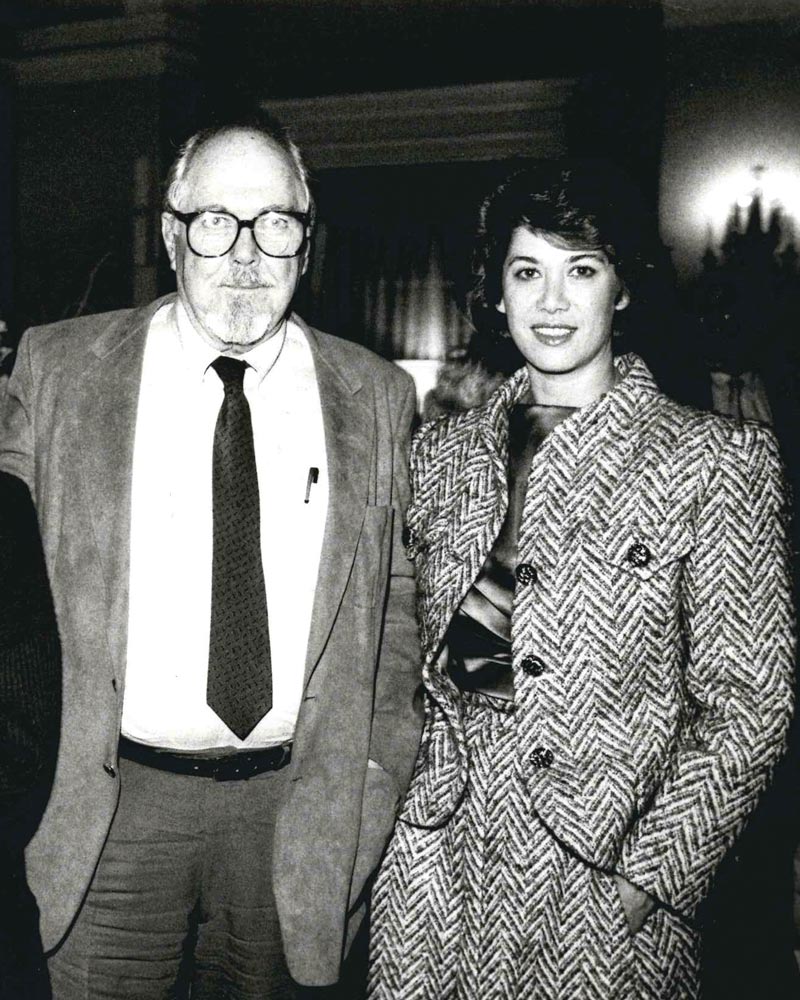

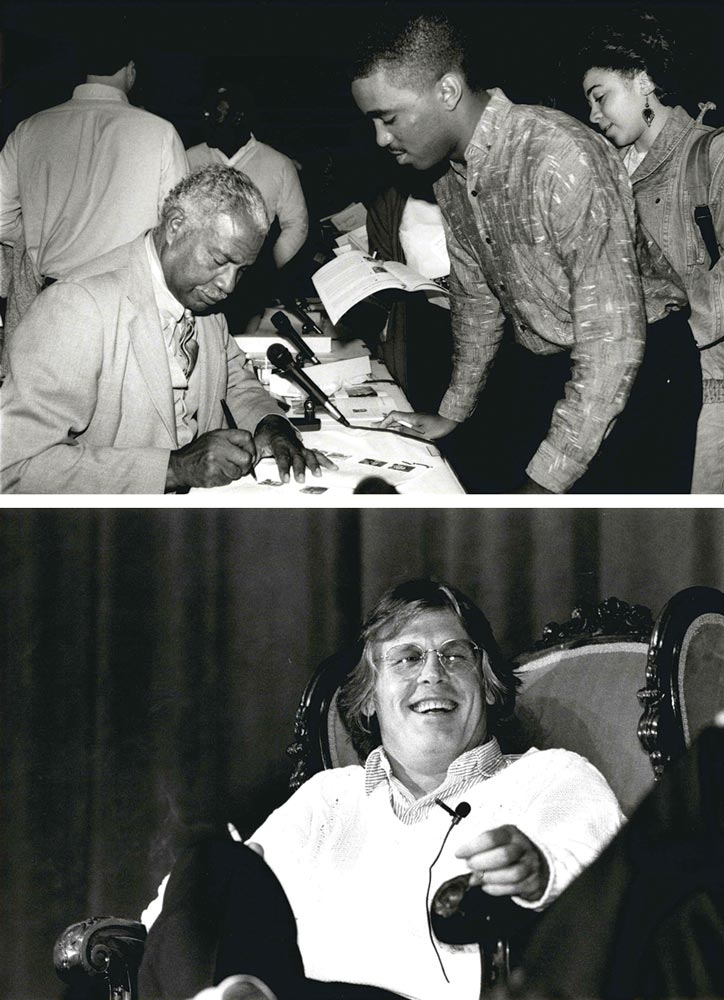

The inaugural festival, in 1988, carried the title “Virginia Festival of American Film” and featured an opulent black-tie gala at the Kluge family’s Charlottesville estate and appearances by director Robert Altman, actors Ossie Davis and Nick Nolte and writer Norman Mailer.

It was a splashy, but unsustainable, opening for a festival that scaled back its ambitions—and more importantly, its expenses—in the following years. There was no guarantee in those early years that the festival could sustain a quarter-century run.

Movie producer Mark Johnson (Col ’71), whose record in Hollywood includes the 1989 Academy Award for Best Picture for Rain Man and an executive producer credit for the critically acclaimed TV series Breaking Bad, witnessed the festival’s stabilization and recent growth firsthand as the longtime chair of its advisory board. “At an early point, I was worried the festival wasn’t going to make it,” Johnson says.

During Herskowitz’s tenure, the festival continued to choose an annual theme, as it began doing before his arrival, to guide the selection of films shown each year. “We decided that each year was constructed as a course, really, on a film studies topic in which the whole region was invited to enroll,” says Herskowitz.

The VFF’s adherence to annual themes also inspired some nontraditional screenings. In 2002, the festival’s theme was “Wet,” which led to a screening of Jaws at UVA’s Aquatic and Fitness Center. Filmgoers watched the movie while floating in the pool on inner tubes.

When Herskowitz stepped down in 2008, moving on to direct the University of Oregon’s Cinema Pacific festival, VFF found his successor the following May in an ambitious Florida native and former actor. As founding director of the Sarasota Festival in Florida, Jody Kielbasa had a 10-year record of building what became one of the top regional film festivals in the United States, with more than 45,000 tickets sold in 2008.

A New Era

“Certainly the festival has a long history of substantive discourse and remarkable panels. It’s always been known for that, and in no way have we changed that in the last four years other than to reinforce it,” Kielbasa says.

But longtime VFF attendees noticed that something new was going on when in 2010, Kielbasa’s second year at the helm, the festival announced it would no longer tie its programming schedule to a single theme.

“I know that there were a lot of very successful years coming off the annual themes, but I think we were able to explain to people that we’re getting more rather than less,” Kielbasa says. “My interest was in screening a festival that was composed of the very best films in any given year and really opening the floodgates and exploring a much wider variety of themes. This festival used to screen about 60 or 70 films, and we’re screening more than 125 films now.”

The festival’s schedule also includes a Family Day of free screenings of family films, a Young Filmmakers Academy for elementary- and middle-school students, and an annual screening of documentaries for area high-school and middle-school students, bookended by an opening-night gala and a “Late Night Wrap Party.”

Creative programming, like a 2011 discussion between director Oliver Stone and Professor Larry Sabato (Col ’76) after a screening of Stone’s JFK, has pumped new vitality into the event, says festival advisory board member John Harris (Com ’82). “You don’t see guys like Woodward and Bernstein at other film festivals,” says Harris. “And you might see Oliver Stone at other festivals, but you won’t get him talking with a Larry Sabato onstage about all the intricacies of the Warren Commission.”

“[The student] was trying to drag his mom to see this film again the next day because he’d had such an ‘a-ha’ moment,” Evans says.

Academic Buy-In

The University’s academic departments have welcomed the festival’s willingness to incorporate their areas of expertise into the event’s programs.

A screening of Locked Out, the UVA Center for Politics’ documentary on the movement to close Virginia schools to try to prevent desegregation five decades ago, was followed by a panel discussion featuring Sabato and former Virginia Gov. Douglas Wilder.

The festival has reached out to students on Grounds in recent years as well. In 2010, Peter Bogdanovich, the writer, film historian and director of the Oscar-winning films Paper Moon and The Last Picture Show, sat in on University classes, led film lectures for UVA students and offered feedback on student film work.

VFF’s program manager, Wesley Harris (Col ’08), who majored in media studies with a minor in film studies, recalls how as a first-year student he sampled only a few festival films screened on Grounds.

“One of the areas where we’ve improved the most is making ourselves more fully visible and available and not intimidating to students,” says Harris, a former festival intern. “Building on that, we’ve opened our doors much wider to more student participation.” A record 8,700 student tickets were issued to the 2012 festival, and each year, 12 to 14 UVA students earn three independent-study credits working as festival interns.

Harris is one of two University graduates who now work on the festival’s small full-time staff out of a modest, second-story office on Charlottesville’s West Main Street. Next to his desk hangs a large dry-erase board that serves as the “war board” where he and Kielbasa map out the calendar of films booked for the festival.

“It’s like laying out a shopping mall,” Harris says. “You don’t put your anchors in the same place when you’re laying out a city block, and you don’t screen certain films at the same time. We announced last year’s schedule on Oct. 2 and two days earlier Jody and I were standing at this board at 9 o’clock at night, adding films at the last minute.”

Like Harris, managing director Jenny Mays (Col ’03) was a festival intern as an undergraduate student. “I remember before I started interning here, just from observing the festival and attending events, being in awe of what they were able to bring to a small college town,” Mays says. “When I started to intern—and I think the interns now still get this feeling, too—you start to realize that very few people are putting on this very big event.”

It’s Not Glitzy—And That’s a Good Thing

Kielbasa says he continues to explore the different nooks and crannies of the University’s community, familiarizing himself with programs, faculty, student initiatives and academic departments across Grounds that may have something new to offer the festival.

That approach, he says, should lead to opening up more opportunities for collaboration, opportunities that will allow him to plan ahead years in advance. At the same time, the need for a sprinkling of star appeal and some screenings of widely anticipated new films to serve as festival tent poles remains.

“Give Jody a lot of credit for being creative,” says Johnson, the award-winning film producer and chairman of the festival’s advisory board.

Many of the festival’s stakeholders see the festival’s focus on filmmaking and discussion, rather than glamour, red carpets (and the jewel heists that can come with it), as its strength.

“It’s not glitzy; it’s not the place to be seen, but it’s a very serious festival,” Johnson says. “Until recently, it was undiscovered, but now a lot of the film business, press and serious moviegoers are discovering it.”

Highlights Reel

Richard Herskowitz, Jody Kielbasa and Wesley Harris discuss memorable film screenings from the Virginia Film Festival.

Herskowitz

During a screening of Martin Scorsese's Raging Bull, an opera aficionado in the audience pointed out how the aria playing in the background of one scene paralleled the film's plot. Ebert started pausing the film every time the music began to swell and said, "Hey Opera Guy, what are we listening to?"

Kielbasa

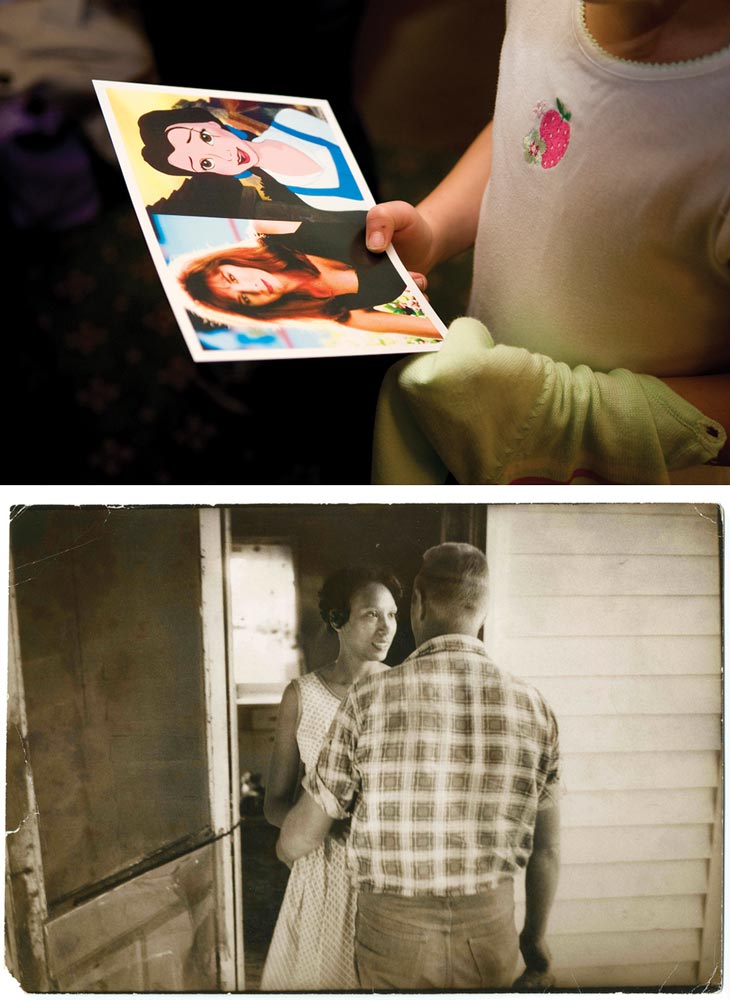

The Loving Story [a documentary focused on Richard and Mildred Loving and the landmark 1967 Loving v. Virginia Supreme Court case that led to the legalization of interracial marriage in all states] was an important film for us. We screened it for local high schools and middle schools, and the students couldn't believe that a mixed-race couple would be breaking the law. We had the original ACLU lawyer who argued the case before the Supreme Court back in 1968, and we had the Lovings' daughter, Peggy Loving, in to talk about what that experience was like, growing up with her parents. The kids gave them a standing ovation.

Harris

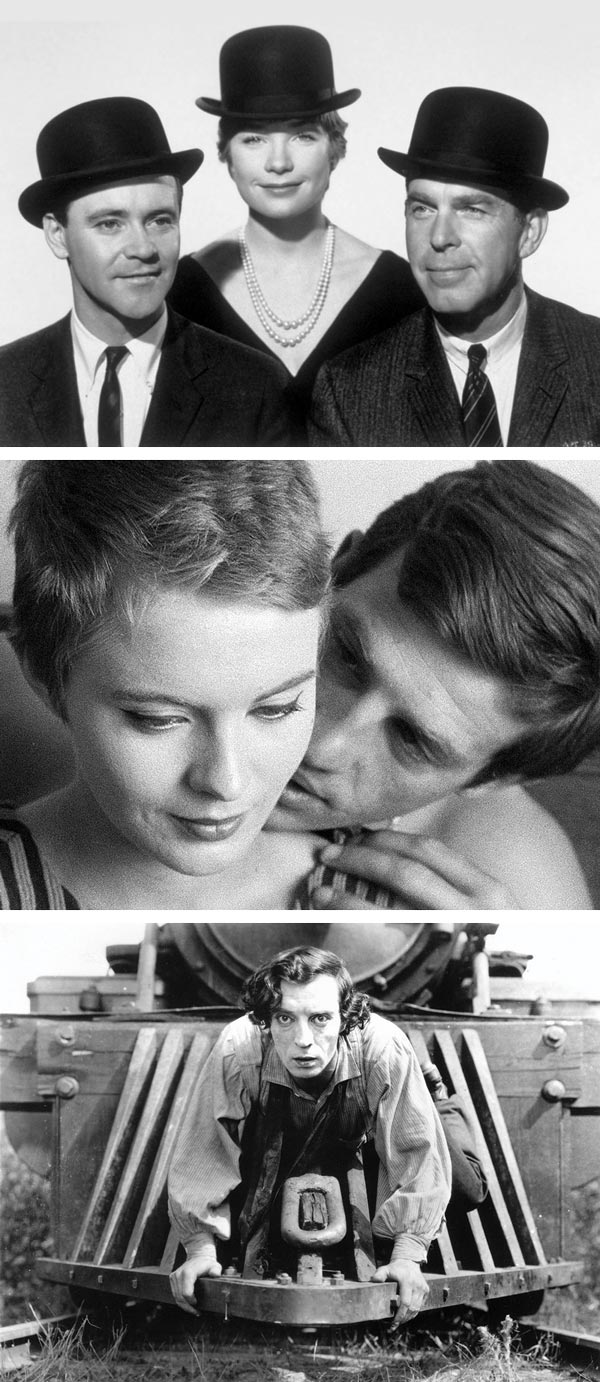

Billy Wilder shot The Apartment in a restrained black and white to focus on this lonely man, the Jack Lemmon character. He used a big, wide frame to explore the vacuous nature of working in an office, of living that life.

With Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless, a new 35-mm print of it had just been made, so we were one of the first places to show that to an audience. And it was the first time an audience had seen a new print of that film in decades, which is sort of funny, because it's a very purposefully lo-fi film. It's grainy, shot on 16-mm and consciously had a rough edge to it. It was strange and interesting to then see it pristine.

One of my favorite moments in The General, Buster Keaton's 1926 silent film that we screened in 2011, is a scene late in the film. It's understood to be the most expensive shot in film history up to that point. It's a shot of a locomotive running off a bridge and crashing. They achieved that shot by actually running a locomotive off of a bridge and crashing it.

The amazing thing about that sequence is that that's not the punch line to that scene. The punch line comes when it cuts from that train crashing to Keaton's deadpan, stony face. That's when the laugh happens. So the most expensive shot in film history up until that point was a preposition. It was serving the purpose of nothing but a shot of a face … It's just such a slick, smart way to compose a sequence, and it apparently came naturally to Keaton.