Looking Back to Look Ahead

Study of nursing history provides insight into future of health care

When Arlene Keeling (Nurs '74, '87, Grad '92), a UVA nursing professor, was completing her Ph.D. coursework at the University, she took a History of Health Care course taught by Professor Barbara Brodie. "That class introduced me to the fascinating and often undocumented work of nurses in the past," she says. "It introduced me to a set of nurse ancestors who had done remarkable things in communities and in hospitals throughout the nation." Keeling changed her research focus to what she calls "the cultural DNA of the nursing profession," investigating the history of coronary care in the nation (from a nursing perspective). Today she is director of the Eleanor Crowder Bjoring Center for Nursing Historical Inquiry at UVA.

In Keeling's view, the growing emphasis on history will result in rewards for the health care field and for patients alike, especially with changing practices and policies. For example, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), passed into law in 2010 (with provisions rolled out over a 10-year span of time), greatly expands the number of Americans who will have health insurance or Medicaid benefits, but it also increases the scope of coverage and places a greater emphasis on preventive services such as mammograms and flu shots.

Leaders at the Bjoring Center point out that new national policies such as the ACA can enable nurses to, as Keeling puts it, "practice to the full extent of their training," which might include anything from working more directly with communities to exercising more prescriptive authority (in the case of nurse practitioners). "Sometimes, the study of nursing is not about evolving; it's about stating what we've done for a century and then reusing that knowledge," Keeling says.

The Future by Way of the Past

When the center first opened, developing a body of nursing history proved difficult. "We set for ourselves the task of trying to find and preserve and make available the things that nurses had done," Brodie says. Initially, this included revisiting nursing textbooks at various points in history to see what nurses of the past had been taught. But to Brodie, "the most entrancing history is the story of what people did in certain times and under certain conditions—as real human beings dealing with real human problems in their best ability to serve." Today, the center has acquired numerous personal and organizational primary sources that tell not just the stories of what nurses have done, but how and why.

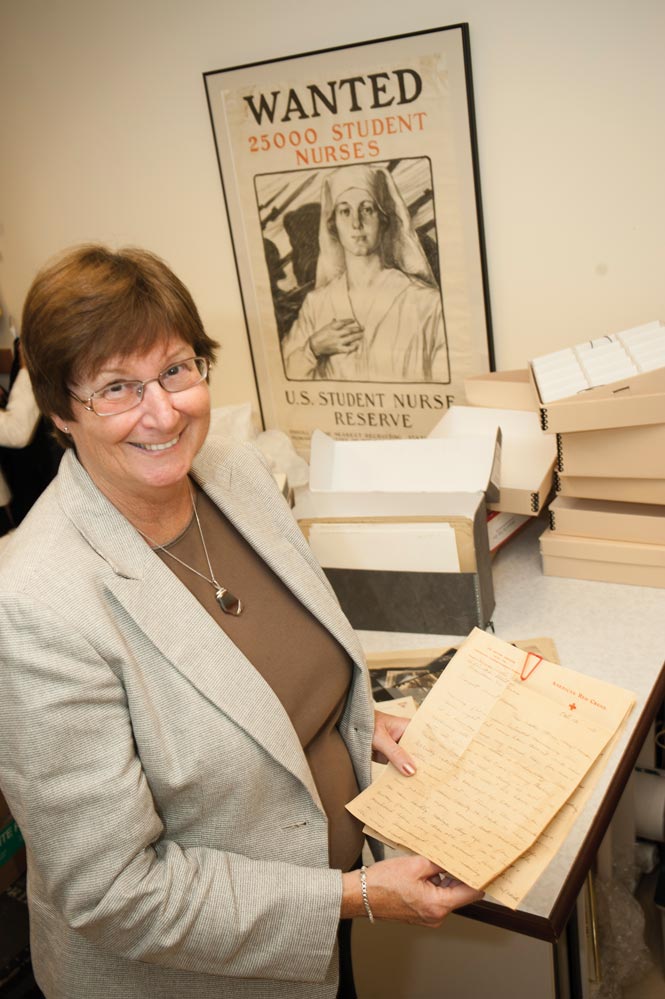

At the center—housed in the School of Nursing's McLeod Hall, and recently re-named after benefactor Eleanor Crowder Bjoring, who is known for her decades of work promoting and teaching the history of nursing—students can peruse an impressive collection of firsthand materials, many of them digitized.

The center's Nancy Milio Collection—composed of photographs, newspaper clippings, an audio interview and a personal journal—tells the story of nurse Nancy Milio's efforts to establish a clinic, the Mom and Tots Center, in a predominantly African-American neighborhood in 1960s Detroit. Through this collection, students can gain a better understanding of how communities and nursing professionals have historically worked together to help underserved populations obtain good care—some of it preventative—from people they trust.

Another, the Benoist Collection, documents the experience of public health nurse Caroline Benoist in Mississippi in the 1930s and 1940s. This collection provides valuable insight into maternal and child health care in Mississippi during the Great Depression.

To help bring history into view, the Bjoring Center also regularly updates a window display featuring important moments in nursing history, such as the depiction of a segregated African-American maternity ward in the 1930s or a scene of young schoolchildren lining up for polio vaccines in the 1950s. Recently, the window depicted a nurse anesthetist working with Dr. Alfred Blalock on "blue baby" surgery at Johns Hopkins in 1943. Plans for the future include a display of nursing during World War II—a scene that may include the cap and cowl of Army nurse Mary Elizabeth Finnegan, the mother of UVA President Teresa Sullivan.

A Window in Time

Keeling and her colleagues incorporate a study of history into the nursing program curriculum; for example, Keeling currently teaches a course called Historical Inquiry in Nursing. In discussing disasters in particular, Keeling explains that, as with many other fields, "the lessons learned from one disaster can be applied to the next," making the study of historical context invaluable to informing current practice and health policy.

For example, in her book (co-authored with Barbra Mann Wall) Nurses on the Front Line: When Disaster Strikes, 1878–2010, Keeling discusses the critical role nurses played in the 1918 influenza pandemic, teaching what the book describes as "key principles of respiratory hygiene, hand washing, disinfection of household utensils and the critical importance of wearing gauze masks in public." Many of the lessons learned from the 1918 pandemic, Keeling says, were apparent in the swift response nurses had to the last pandemic, H1N1, in 2010. In the Institute of Medicine's 2010 report The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health, school nurse Carolina Sandaval is credited with first alerting authorities to an outbreak of H1N1 in her New York City high school, "prompt[ing] a worldwide alert for what would soon be declared a pandemic."

Many UVA nursing students attend the University's Nursing History Forums; recent talks included sessions on nursing in migrant camps during the Great Depression and on care for disabled children in 1907 Seattle. The specific setting in which nurses practice may change, but one thing does not: the role of the nurses themselves. Working in collaboration with rural physicians, nurses have long been responsible for providing reliable health care to people from vastly different backgrounds and with vastly different needs, some in remote areas.

Nursing and National Policy

"We can't exist as a civilized society without nurses," says Jean Whelan, assistant director at the University of Pennsylvania's Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing, the other major U.S. center for the study of nursing history. "I like to use an analogy: When a nurse gets a new patient at the hospital, the first thing she or he must do is ask about the patient's history—what brought you here, what made you sick, tell me about your history. The same thing holds true generally for nursing. We need to know where we were so we can figure out where we should go in the future." Whelan, also an adjunct associate professor at Penn's School of Nursing, has focused her research on the nursing workforce in the 20th century and the policy decisions that have helped or hindered adequate nurse services.

From studying the nursing workforce trends of the past, Whelan warns that when the country has a shortage of nurses, which happened throughout the 20th century, strategies to meet the shortages were put in place that were not conducive to good health care. "After World War II, there was a switch, where instead of having a lot of nurses working the hospitals, you end up having fewer nurses and more ancillary personnel," Whelan says. The shortage continued through the 1950s, '60s, and '70s. Rather than directly caring for patients, Whelan says nurses instead spent much of their time directing assistant personnel around. "That really diluted the quality of nursing care," Whelan says.

Keeling agrees, emphasizing that registered nurses, public health nurses and family nurse practitioners are poised to be valuable partners and leaders of the developing health care models. "Policymakers today should not overlook the central role nurses have long played in providing access to care for numerous underserved populations," she says.

A World of Knowledge

As the Bjoring Center expands its scope, the emphasis on historical inquiry prepares students to ask questions that might lead them to new knowledge and insights outside of UVA. Graduate student Pamela Kimeto (Grad '18) is currently investigating the history of nursing in British colonial Kenya in the 20th century, and credits UVA with offering a greater breadth of nursing history study than she had received at other institutions. She also notes that the center helped her learn to use primary and secondary resources—skills that have aided her in searching elsewhere for material on her topic.

Beyond specific and practical applications, the center believes history helps instill in nurses a sense of pride, and can remind nurses of the importance of compassion, ethics and responsibility in their profession. "We stand on the shoulders of our foremothers," Brodie says, "and in the end, in all things, knowing on whose shoulders we stand matters."