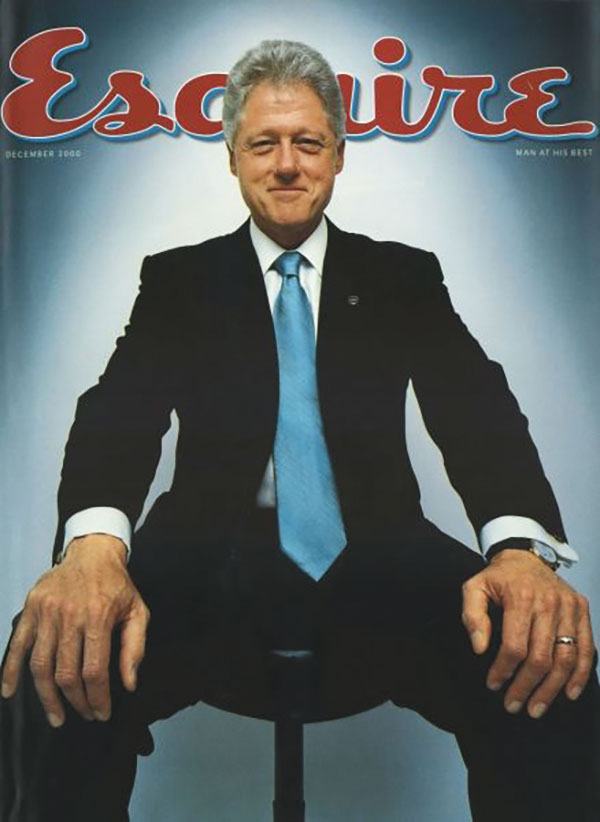

‘I made a good magazine’

Former Esquire editor David Granger (Grad '81) sits down with us on his way to the Hall of Fame

David Granger (Grad ’81) ran Esquire as editor-in-chief from June 1997 to March 2016—ran it with an unshakeable faith in the power of a men’s magazine to inspire readers, change the world and sell a nice suit.

During his run, Granger infused the title with a strong voice, a bit of swagger, a larcenous sense of humor and, with some of the best creatives in the business, drop-dead good looks.

Esquire also published gorgeous writing. Granger demanded it. His Esquire made the finals for 72 National Magazine Awards and won 17 of them, including General Excellence in 2006.

This spring the host of those awards, the American Society of Magazine Editors, inducts Granger into its Magazine Editors’ Hall of Fame. He was my editor for 25 years. Virginia Magazine asked me to catch up with him. This Q&A, edited and condensed, comes from our recent lunch together at Da Tommaso on Eighth Avenue in New York, an old Esky favorite.

When did your UVA days begin?

I think I started there in the fall of ’78. My dad had been in academia and worked as a dean, and because all my role models through college had been professors, I thought I was going to teach. I applied to three schools to get a master’s. Texas offered me money, but I ended up going to UVA, probably because—well, when I went to visit University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, I just didn’t understand the campus. I had a bad experience, and I think I had a bad guide. I had great experiences at UVA—it’s a really impressive campus. Mr. Jefferson’s University—they’ve got the Lawn. It looks like what college is supposed to look like.

How was life as a grad student?

I was daunted. All my teachers at Tennessee had said, “Wow, you got into UVA—nobody’s gotten in there before.” I was a very good student my first semester. I had some amazing professors. And in preparation, before I went, I read as many of their journal articles and stuff as I could, and I guess maybe by reading articles in academic journals, I didn’t get the most exciting view of what the academic life could be. The topics seemed small. Doubt about whether I was going to become a professor started to creep in. I wanted a broader canvas, something that more people would read and experience. I wanted it to be artistic, but I also wanted it to be broad, and I think that’s when I started thinking about the Esquire magazine I started reading in college.

You and I met when you were already at GQ, editing features. How’d you get there?

In my first 10 years in New York, I had seven full-time jobs. I started at Muppet Magazine, the quarterly humor magazine for children age 8 to 12, where I got to do a little of everything. But I wrote book reviews as Rowlf the Dog, among other things. Got fired from that job.

Why fired?

I wouldn’t answer Katy Dobbs’ phone. I was the only editorial employee other than Katy Dobbs, who was the editor-in-chief, and I was supposed to be her assistant. I found it much more interesting to actually do editorial than, say, answer her phone. She explained to me that she felt Muppet Magazine was limiting to me, and that in about two weeks, I needed to, you know, go out and explore.

I know ESPN guru John Walsh played a pivotal role in your magazine career. How’d that happen?

I met Walsh after I got fired from Muppet Magazine. He took the call and said, “Meet me for a drink.” I had $11 for the weekend. Walsh said, “What do you do?” I start talking about freelancing for The Village Voice, writing humor columns for the new sports section. That was my writing, aside from being Rowlf the Dog. I’m still nursing my beer, and he has one vodka, two vodkas, three vodkas. I reach for the check and he says, “How much money do you make?” I say, “Well, when I had a job, I was making $9,000 a year,” and he says, “Nobody who makes $9,000 a year is buying me a drink.”

He hired me to be his researcher on this book contract he’d just gotten to write a history of the Heisman Trophy. He was unemployed. And, as you know, he went on to basically run ESPN for 25 years. I’d found my guardian angel for the next three jobs.

When we met in ’92, you were a hungry young GQ editor. Clearly, you felt ready to run your own magazine. Was Esquire always your dream job?

I’d always loved Esquire. It was my first magazine as a man to read. I always thought, when I came to New York, I’d work at Esquire. And I couldn’t get an interview at Esquire. And it was dying—you could see that from the perch at GQ. After four and a half years at GQ, I’m 39 years old, and it was like, I gotta make a play for this because if I don’t get it now, somebody’s going to take it over and fail, and it’ll go away, or someone will take it over and succeed, and then 10 years from now, when that guy dies, I’ll be too old. That was when I wrote to Cathie Black, the president of Hearst’s magazine division, and a year later, I got a call.

And wound up spending almost 20 years bringing Esky back from the living dead.

I made a good magazine. The last couple years at Esquire, people interviewing me would ask about my legacy. I’ve never believed in legacy. We do what we do. We pretend it’s important at the time, and if you get some acclaim and your product is successful, bless you. Six weeks after I’m gone, it’s freaking over. Your last issue’s off the newsstand, and it’s over.

Yes and no. In a way, your real-life legacy was that standing ovation.

You’re talking about the National Magazine Awards. In 2016.

Everyone knew you’d been canned—

Yeah. It had come out that I’d been fired at Esquire, and we were nominated for one or two or three. I had not wanted my firing to come out prior to the awards, but it did. It came out. And it turned out to be fantastic, because there’s always that little halo of victimhood that surrounds a firing. And then we got lucky enough to win—I think it was the essay category.

The first thing I said was, “This makes me so happy, I’m just going to quit.” But on the way up to the stage, people rose and they gave me a standing ovation, which was freaking amazing. You can’t believe it when it’s happening. And if the timing hadn’t worked out, it never would have happened. Thank God it leaked that I was getting fired.

You were a great leader, truly. No one got to the office earlier. No one worked harder. It was leadership by example.

Well, it was more leadership by fear.

Fear of getting fired? Of failing?

I never worried about getting fired. I was worried about failing. I was consumed with the knowledge that I was going to fail. It wasn’t fear that I was going to fail. It was knowledge. It was certain that I was going to fail. And after like three years of being second-guessed by various people in the corporation, one of the great moments of my life came when I was driving home. I think it was the first new car I ever bought, when I got the job at Esquire.

The Jag?

I wish it had been the Jaguar; it would have been a better story. It was the last model year of the Lincoln Mark VIII, and we had been out somewhere. It was around the holidays, and I knew Hearst had this policy that they wouldn’t fire me between Thanksgiving and New Year’s. I was driving home, and I was just so pissed off about work and so certain that I was going to be fired when we got back in the next year. I was speeding up the West Side Highway, and Melanie knew what I was stewing about. And she looked at me and she said, “David, just edit like you drive.”

After that, I resolved, OK—I knew I was going to get fired—and I thought, “Let’s not do anything that I’m not proud of, ever again.” That was a good moment.

After almost 20 years running a magazine calling itself “A Man at His Best,” you must know all there is to know about bars, restaurants and fashion.

That’s a myth. I don’t know the best bar—I had to ask. That was the best thing about being the editor of Esquire: I had people who knew something about restaurants, knew something about clothes, so I’d ask them. I never wanted to buy clothes because they were expensive. I bought clothes because they made me feel confident. Like on this shirt that I’m wearing right now, it’s monogrammed. It has my initials on the tail of my shirt. It’s not on the breast, not on the cuff. It’s on someplace that nobody else can see. But when I see it in the closet, I know that shirt was made for me. This is my shirt. Nobody else will ever know it’s monogrammed. I didn’t monogram it for anybody but me.

And that’s what I think manhood is. You do this stuff because it allows you to be more fully yourself—not so that anybody else knows it, but to allow you to be more fully yourself. The monogram thing, it’s a metaphor, man.

I could take my pants off and show you the monogram if you want.

Yeah, we’ll let the fact-checker at Virginia Magazine take care of it.