Back to the Future

Warren Manning’s 1913 master plan made an indelible imprint on how the University looks today

By the turn of the 20th century, the University of Virginia needed a plan.

In the decades after the University’s cornerstone was laid in 1825, UVA grew far beyond Jefferson’s initial vision of the Academical Village. Professors had begun adding on to the backs of their houses. Buildings like Brooks Hall and the Chapel popped up near the Lawn. Classroom and student residential space came at a premium.

Then the Rotunda, the centerpiece of Jefferson’s Academical Village, burned. The Annex was destroyed.

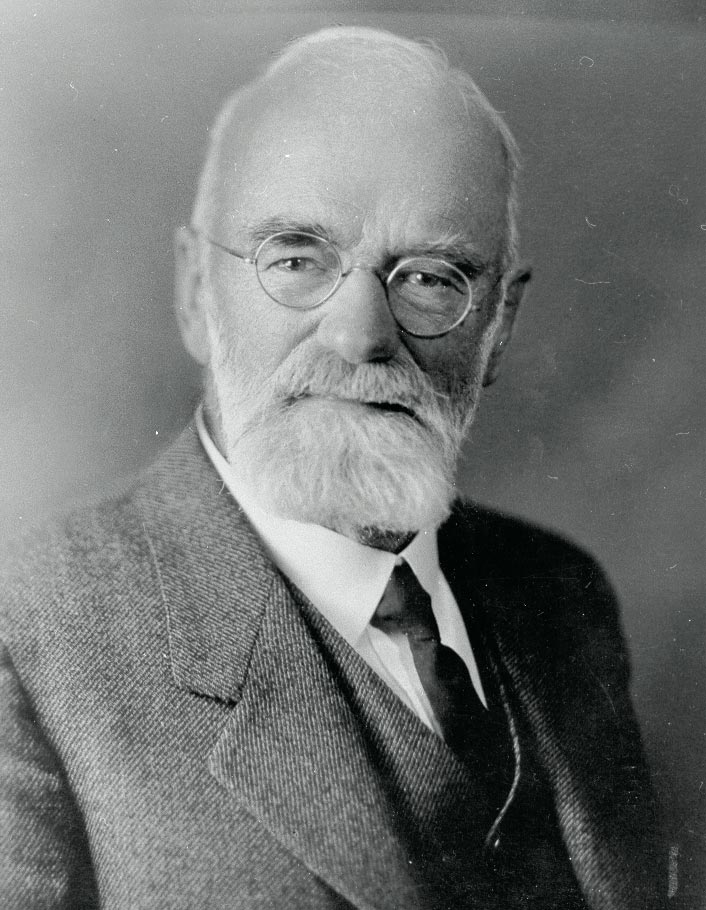

In 1908, the Board of Visitors turned to Warren Manning, a landscape architect from Boston who learned his craft from Frederick Law Olmstead, widely considered the father of landscape architecture.

The Board asked Manning to develop a master plan for the University, to keep growth in line with Jefferson’s intentions.

Master plans are meant to be a vision statement, identifying a current space and its uses while projecting some idea of future needs. Manning was honored by the commission. He had a strong affinity for Jefferson as a “gentleman architect” and builder. His unpublished autobiography shows he believed the University’s commission to be one of the most important of his career. The University issued him a five-year contract, paying him $250 annually, or about $6,000 in today’s dollars.

Manning began an intensive analysis of Jefferson’s design intent for UVA, studying plans and interviewing various officials across Grounds.

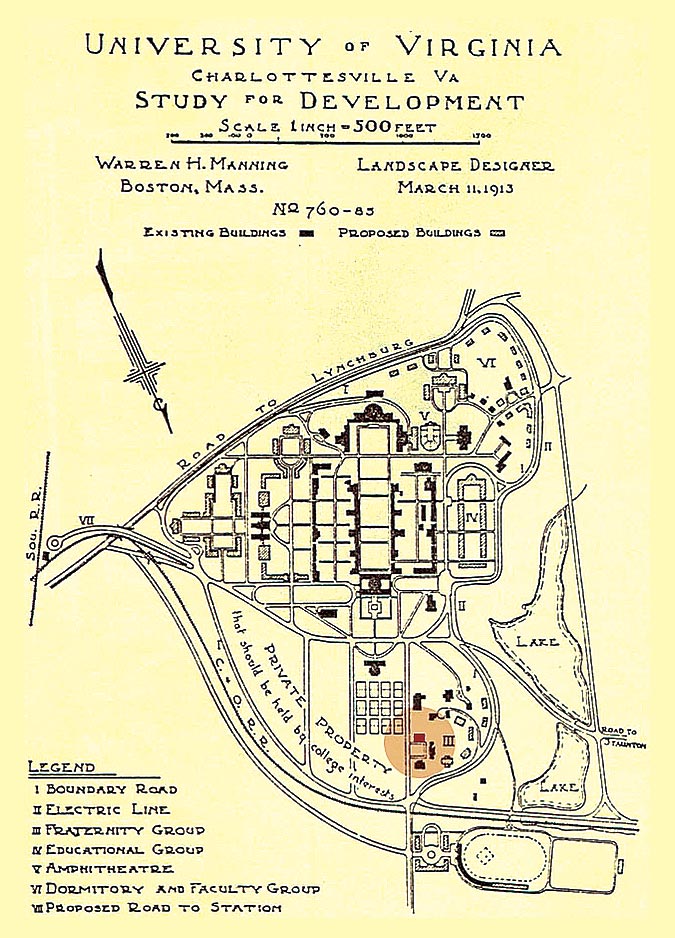

What emerged from his study was a plan to effectively demolish the then burgeoning Corner area, recapture the land for Grounds, and move University Avenue out along the railroad tracks beyond Mad Bowl. The road would have then run parallel to the railroad tracks across what is now Route 29 and continued west.

Route 29, meanwhile, would have come up over Carr’s Hill at a soft angle to create a plan for enlarged ponds. It would then curve to the west in front of the Rotunda and run to where McCormick Road now sits. The area where the libraries are now would have become an enclosed quadrangle. Manning envisioned two other quads on the opposite side of the Lawn, where the medical school now sits. They would all look similar to the Lawn, as if Jefferson had designed them himself.

Instead of the neat, almost controlled gardens and plantings that have become the signature look of Grounds, Manning proposed landscape that was more wild, more rough and tumble. He wanted Grounds to become an arboretum, the “Garden University of America,” as he told the Board of Visitors.

Only some of Manning’s ideas came to be. The location of the McIntire Amphitheater, Peabody Hall, and even the Chi Phi fraternity house were all suggested by Manning. But overall, his master plan can be judged a success. He defined a way of thinking about growth at the University and raised important questions about building values.

More of his vision may have been followed if Manning hadn’t been such a difficult man to work with. According to his personal papers, he got into a heated argument with the Board of Visitors over a Jefferson-designed building the Board wanted to tear down. He was released from service shortly thereafter.

His firing was a good thing from a purely architectural standpoint. There is a purity to the Lawn that speaks to its origins and even Jefferson himself. Manning’s multiple quads would have had the effect of minimizing Jefferson’s vision of the Lawn; it would have been copied so many times across Grounds that there would be nothing to give the Lawn its special texture.

Manning’s plan succeeded by asking important questions about how to build and expand the University. It looked to the past for clues to the future, delicately balancing purpose, imagination and reverence for Jefferson’s vision.