A Stitch in Time

Former professor’s vision inspires designers from Culbreth to Broadway

While Ann Hould-Ward was a student at UVA in the 1970s, she and one of her professors received trunks of clothing from the estate of a woman who had recently passed away.

The apparel was intended for a clothing collection that professor Lois Garren (Grad ’72, ’78), who taught costume design, was compiling. Inside the trunks, Garren and Hould-Ward discovered a treasure.

“There was a Worth peignoir,” says Hould-Ward (Grad ’78). Charles Frederick Worth was a 19th-century French fashion designer whom many consider the father of haute couture. Hould-Ward would go on to use the peignoir as the basis for a graduate project. Garren would add it to an array of garments that has, over the years, grown in value and meaning.

Garren, who died in 1990, left a legacy that moves in two directions—her example motivated students like Hould-Ward, and her collection of historic clothing has flourished under the care of professor Gweneth West.

“She was a major force in my coming to New York,” says Hould-Ward, who has become one of the theater world’s most renowned costume designers. She also praises Garren’s vision—her cultivation of the collection so that students might find inspiration there. “So much of what we do is about the inner construction of something. To be able to look at the real things, to be able to see them … a piece of clothing shows you how people thought at the time. As a student you can see that, and it’s very influential about how you go about being a designer.”

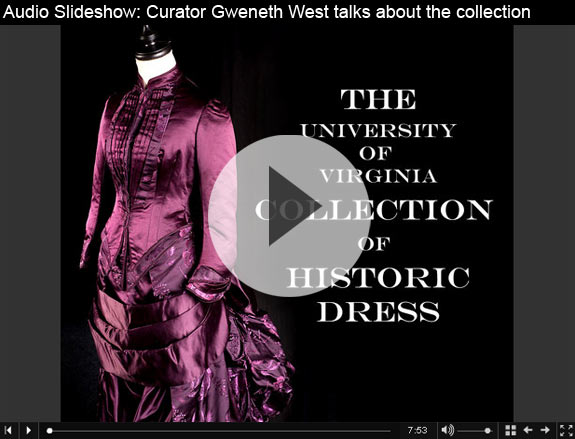

And so Garren’s legacy also lives in the University of Virginia Collection of Historic Dress, which West uses for costume design and history classes in the drama department. Like Hould-Ward, she was inspired by Garren’s vision as well as her personality. “She was delightful—she had a friendly, infectious laugh. There wasn’t anything about the creative process she didn’t love,” West says.

Collecting history

The collection, which includes more than 1,000 pieces, had inauspicious beginnings. In the mid-1960s, Garren, a part-time costume designer, was persuaded to join the faculty to teach classes in costume design and construction. At the time, the collection consisted of castoff clothes, donations from citizens who, for instance, couldn’t bear to throw away their loved one’s World War I or II uniforms.

It was Garren who saw the value of these artifacts. She went through them, cultivating an assortment of garments that would eventually encompass a wide spectrum of periods. There are 1830s Romantic dresses as well as a silk 1860s crinoline gown with cotton eyelet bishop sleeves. There’s a slave dress, a collection of 1900 Edwardian laces and garments from China and Japan.

Donations continue to come in, and as curator West must carefully assess contributions, whether they be T-shirts, trousers, business suits or gowns, to find those special pieces that will say something about our times. “What do we keep of contemporary fashion so that it will be this ubiquitous symbol of what was worn?” asks West.

For example, among the elegant gowns of the collection is a simple circa 1834 cotton dress that someone with an untrained eye might have discarded. Closer inspection reveals the utilitarian nature of the garment, which has a pattern that masks stains and an opening in the right breast area for nursing. This kind of dress says as much about the lifestyle of women from a certain era as any formal wear might.

The collection yields other treasures. Not long ago a gentleman donated an outfit he said was worn by a relative on a boat. West had the fleeting idea it was a leisure suit, as in the kind worn on a cruise ship. It turned out the man was talking about a different kind of boat, probably one coming from England about two centuries ago. The outfit consisted of a man’s woolen coat and breeches dating to 1795. It’s the oldest men’s garment in the collection.

Tactile value

In the Internet age, where photos and information are posted on Web sites, the value of an actual, three-dimensional collection is clearly evident. “What is unique about a collection like this is that you can touch it, and feel the fabric and see the way it was built,” says West. “When you actually experience it, it shifts your feelings about artifacts; it becomes an experiential opportunity that we’re very distanced from in books.”

The collection offers tactile experiences that would most certainly contribute to one’s understanding of costume design. Students can study how certain fabrics drape on their hand. They can observe how certain textiles will cinch when stitched and study the intricate inner construction of a simple-looking piece.

Having access to such a hands-on experience benefited Hould-Ward. Along with winning a Tony for Beauty and the Beast, she has received costume-design nominations for Sunday in the Park with George and Into the Woods, and in 2008 was nominated for a Drama Desk award for A Catered Affair. She’s designed costumes for theater, opera and ballet companies, as well as for more than 100 regional theater productions across the U.S.

Garren’s personal experience proved as much an inspiration for Hould-Ward as the clothing. Garren was able to spend a number of summers in the big city exploring the theater world, and she was able to pass that knowledge and experience to her students. “The theater in New York is an entirely different beast,” says Hould-Ward. “A lot of teachers wouldn’t have been able to do that. I don’t think she ever realized what an inspiration she was.”

Dramatic inspiration

Imagine doing several years of painstaking research on a certain time period to create a set of costumes—obtaining the right fabrics, overseeing the intricate construction, the endless fittings. What might it be like to finally see life breathed into your creations on opening night?

For Hould-Ward, the moment when everything comes together happens well before there’s an audience. “For me, there’s a moment in the technical rehearsals when I see that I’ve got something. That, yes, I’ve made something beautiful and the audience will get what I’ve wanted and planned and pushed for.” After that, she says, she steps out of the way. “I’ve made a child, I’ve seen it through, I let it go.”

As for favorites, Hould-Ward maintains that every production is special in some way. But she does mention Sunday in the Park with George, a musical inspired by a Georges Seurat painting, with a certain fondness. “The opportunity to do research in that regard was quite wonderful, to look at the painting to the depth that we did.”

As in any artistic endeavor, there are growing pains along the way. “There’s always the angst of getting it done,” says Hould-Ward. “We’re talking about several million dollars’ worth of clothes; that in itself is a burden, a responsibility.”

When asked about some of the difficulties involved in putting together a production, Hould-Ward cites a hardship afflicting many industries at the moment—the economy. “That’s the biggest thing that’s happening currently,” she says. “Entertainment is suffering from the finances of our world. I had six large commercial projects cancelled in three months after the demise of our economy.”

Regardless of the vicissitudes of the industry, with a given project it’s the initial stages of creation that Hould-Ward thrives on. “I love to draw, so I really love being at the drawing board,” she says. “I love choosing the fabrics. I love all the different aspects.”

Preserving the past

While Hould-Ward thrives on creation, West’s major challenge is preservation. Fabric, unlike the clay or steel of other pieces of art, can deteriorate quickly, particularly given the circumstances of UVA’s collection. The garments are stored in a room in the nether regions below Culbreth Theatre; the space lacks controls to regulate humidity, dust and other variables.

Also, as time passes, some of the dresses on hangers will begin to fracture at the shoulder. “You can’t just fold them up and put them on a shelf,” West says, “because wood produces an acid that can harm the clothes. They need to be in acid-free boxes, which are expensive to procure and difficult to store. The verdict is still out on what all these plastics and polyesters are going to do when they age.”

But it’s worth it. Not only does such a collection have the ability to inspire students, but as with any historical collection, it reflects something of ourselves. Says West, “We try to figure out what we know about the person who might wear a certain garment, and then we look at our own taste and why we chose clothes and what it says about us.”

More from the UVA Collection